Changing Lanes at the Speed of Life

- Dr. Richard Lazenby

- 21 hours ago

- 6 min read

Updated: 21 minutes ago

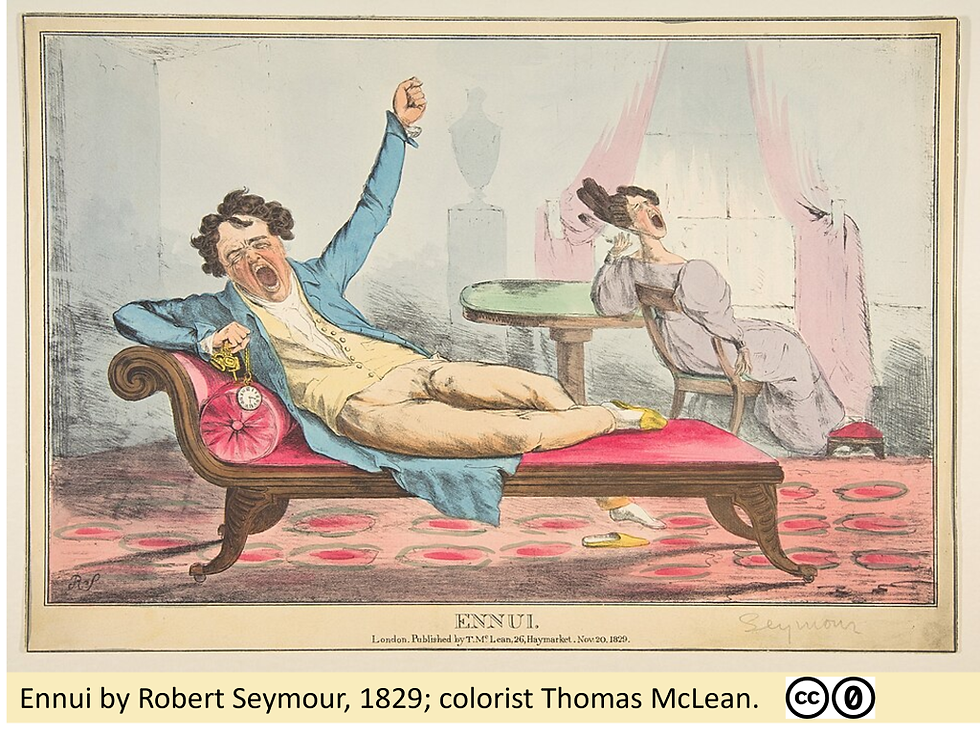

Living in the fast lane is linked to boredom proneness

Who doesn’t get bored from time to time? Everyone does! But it is also true that some of us are more prone to boredom than others. And there are two very real considerations here. If you are one of those people, research suggests it is likely that your greater boredom proneness is tied to a negative childhood experience AND that characteristic will also define many choices you make in how you live life as an adult.

Now, if you find that opening paragraph boring, you’re living life in the fast lane. The question is: how did you get there and what does that mean? Better read on…

For several decades now life history theory (LHT) has been a powerful tool for understanding survival and adaptation to various environmental circumstances at the level of species, populations, and even among individuals [see footnote 1]. Within and across these levels, the prime measures of evolutionary success are survival and reproduction, and underlying these outcomes is a startlingly simple equation: what is the balance between capturing ‘energy’ (say through hunting or harvesting … or working and shopping!) and allocating that same energy to those activities or biological processes enhancing the likelihood that more of your genes show up in later generations (such as growth and development, finding a mate, care-giving etc.)! It’s akin to figuring out your weekly household budget so that you don’t spend (allocate) more than you earn (capture). Within LHT, it is generally seen that how we live our lives encompasses trade-offs in energy capture versus allocation, and at its most simple expression, we can invest in traits that enhance survival, or in traits that enhance fertility [see footnote 2]. For example, we can make trade-offs between current vs. future reproduction, off-spring quantity vs. quality, or promiscuous mating vs. bonding and higher parental investment.

One area of wide interest within the LHT paradigm is something called pace of life, broadly seen as a continuum from slow to fast. Pace of life encompasses what is known as a life history strategy – the sum of all the decisions we make vis-à-vis the trade-offs noted previously. And it is not necessarily true that all aspects of our lives fall into one camp, or one position on the continuum. We might live faster in some areas and more slowly in others. But there are generally accepted correlates: we might invest collectively in slower growth and body maintenance, higher off-spring quality and larger parental investment as a means to increase the likelihood of survival and reproduction. Or we might just say, to hell with quality, if I have 15 kids with 5 different women, at least some should make it!

Of course, life history decisions are not made in a vacuum. Our ability to capture ‘energy’ [see footnote 3] will be widely impacted by our external circumstances of life. Is our environment safe and stable (positive), or harsh and unpredictable (negative)? Did our own parents invest generously in our upbringing (positive), or was our childhood fraught with danger and hardship (negative)? Generally speaking, LHT suggests that positive circumstances and experiences would favor a slow life history strategy, while negative ones favor a fast life history strategy. Now, humans generally are in the slow lane relative to other primates, but in some circumstances the fast lane will be more adaptive, for example, in cases in which environmental / ecological instability and socio-political volatility is the norm as is characteristic of some developing countries, or for lower socioeconomic classes everywhere resulting from fewer opportunities and greater barriers.

So, what has all of this got to do with boredom proneness, you might well ask? Well, as noted above, one of the principal distinctions between fast and slow life history strategies is environmental stability. And what really characterizes unstable environments is uncertainty and unpredictability – am I confident that I am going to be able to put food on the table tomorrow? Stable situations sustain the status quo (think in terms of job security, food security, climate predictability, nurturing households…). In stable contexts, there is time and energy to invest in growth and development, relationships, offspring and so forth. On the other hand, unstable situations require flexibility and openness to change, to exploit existing circumstances but be ready to explore new potentially superior opportunities. Previous psychological research suggests that a fast LH strategy is associated with typically detrimental ‘dark personality traits’, such as tendencies toward greater impulsivity and risk-taking, higher social deviance accompanied by short-term thinking, and greater sexual promiscuity, all of which may promote adaptive flexibility in unstable environments. And here is where boredom proneness comes into play…

Being prone to boredom promotes exactly that kind of flexibility, as proposed in a recent paper by South Korean researchers Garam Kim and Eunsoo Choi published in Evolutionary Psychology. They proposed a two-fold hypothesis. First, as a general characteristic, in harsh, unpredictable environments “a lower threshold for boredom could drive more frequent exploration, potentially leading to better survival and reproductive outcomes”. Second, and more specifically, they linked early childhood experiences to a greater likelihood of boredom proneness. This follows from the generally accepted tenet that it is our early life experiences that we use to inform choices pursuant to adopting a fast or slow LH strategy [see footnote 4].

So how did Kim and Choi go about testing these hypotheses? First, they conducted a pilot study of undergraduate university students and then followed up with a larger sample of adults as the main study. Participants (97 students in the pilot study and 298 adults in the main study) completed a series of online psychometric scales assessing boredom proneness and life history strategy (fast or slow) [see footnote 5]. Questions such as ‘Much of the time I just sit around doing nothing’ or ‘Many things I do are monotonous’ examined boredom proneness. LHS was looked at using two different scales, one for cognitive-behavioral traits (e.g., ‘I often make plans in advance’) and one for physical traits (e.g., ‘I don’t have major medical problems’). The researchers also looked at impulsivity (likelihood of acting rashly or taking risks), monthly family income and family resources the participants would have had available to them as children. These would include items such as spending money, food & clothing, discipline, emotional support and love, and role modeling among others – all to consider the role of early life experiences as factors in determining LHS as noted above and in footnote 4. In the main study, Kim and Choi also asked participants to assess future anxiety – that is, how likely were they to anticipate a future of “dread and uncertainty”.

In both the pilot study and the main study, boredom proneness was significantly and negatively correlated with both evaluations (cognitive and physical) of LHS – that is, a person more prone to being bored exhibited traits more typical of a fast life history. They also found that those taking part in these studies who reported lower measures of family resources and support were more likely to fall into the fast life history camp, supporting the idea that harsh early life experiences promote choices consistent with a fast life history. In the main study, future anxiety was significantly and positively correlated with boredom proneness but negatively correlated with LHS. The more likely you are bored, the less confidence you have for a bright future and more likely to live in the fast lane.

So, what’s the bottom line here? Boredom prone people live faster lives. They are more likely to have had harsher, more unpredictable and supportive childhoods and as adults will lean toward choices making for less stable relationships, less investment in their own children, riskier choices, and feeling less secure and more anxious about the future.

While Kim and Choi do not discuss this, the implications of their findings are dire: boredom proneness and its consequences are self-replicating. That is, boredom prone adults, given the choices that define a fast life history strategy, will more likely have boredom prone children… and the circle is unbroken.

Footnote 1. For a recent comprehensive review of LHT, see the article by Del Giudice, Gangstad and Kaplan (2015).

Footnote 2. I’m presenting a very simplified prospectus of LHT here – the Del Guidice et al. paper noted above really gets into it!

Footnote 3. ‘Energy’ should be considered a proxy measure for all of the components of that side of the budget ledger. Additional factors to consider in ‘allocation’ is the space we are able to explore/exploit, mate availability, and so forth.

Footnote 4. This notion has been formalized by psychologist Jay Belsky as “psychosocial acceleration” theory which proposes that harsh, insensitive parenting is perceived by a child as a signal for ecological stress thus promoting choices characteristic of a fast life history strategy: advanced pubertal onset and earlier sexual engagement, short term mating effort with multiple partners, exploitive personality traits, and so forth.

Footnote 5. Psychometric scales are commonly used in research to evaluate personality traits, attitudes, abilities and so forth. Typically a question designed to collect information would have a range of responses such as ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’; known as a Likert scale.

Where to Find the Science:

Kim, G and Choi E (2025) Pace of life is faster for a bored person: exploring the relationship between trait boredom and fast life history strategy. Evolutionary Psychology January-March 1-13 DOI: 10.1177/14747049241310772

Of Further Interest:

Del Giudice, M., Gangestad, S. W., & Kaplan, H. S. (2015). Life history theory and evolutionary psychology. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The handbook of evolutionary psychology – Vol 1: Foundations (2nd ed.) pp. 88-114. Wiley.

Comments